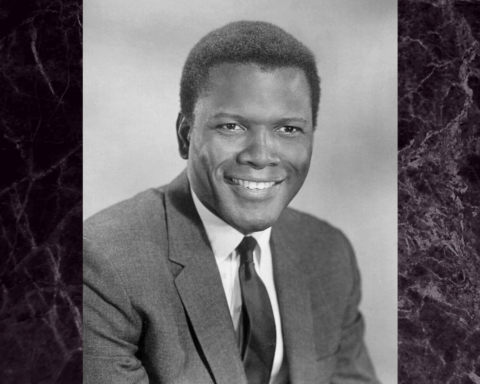

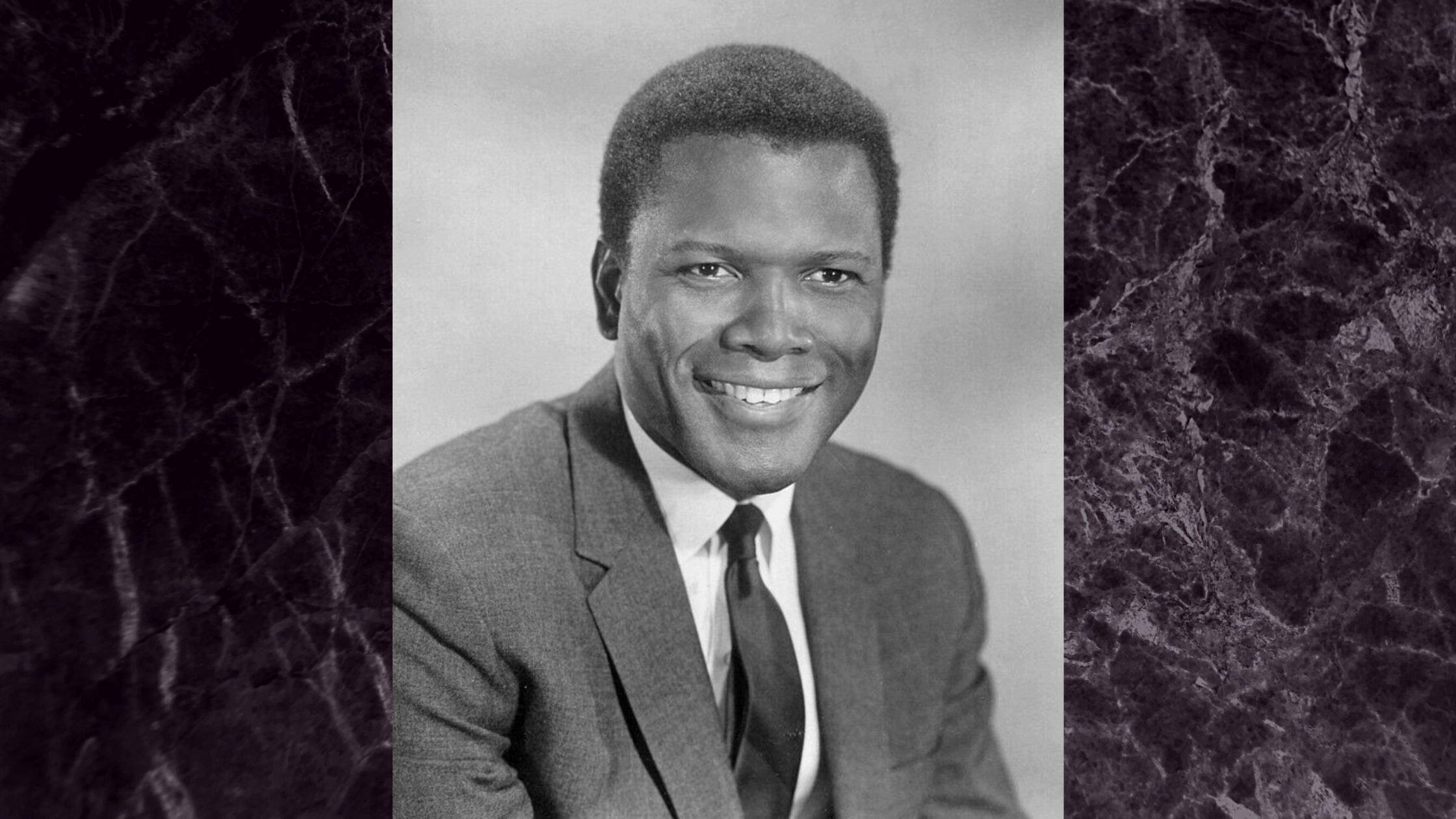

Sir Sidney Poitier: An African Diaspora Icon

Sir Sidney Poitier, a man who is universally renowned for his stagecraft and advocacy passed away on January 6 at the tender age of 94. Sir Poitier’s career has managed to refine the landscape of Blacks in entertainment, with his endeavors being meshed along with the Civil Rights era serving as a powerful messaging force. As we delve into Poitier’s career, we highlight the key moments that solidify him as an icon of the African diaspora.

Poitier was born on February 20, 1927, in Miami, Florida. His parents, natives of Cat Island of The Bahamas, which at the time was a crown colony of the British (until the country gained independence in 1973), owned a tomato farm and often traveled to Miami to sell their harvest. During one of their trips to Miami, Poitier was born, hence slating Florida as his birthplace. He was born three months premature. Once the preemie son of farmers was in assured health, he joined his parents back in The Bahamas where he was raised alongside his six siblings.

At the age of fifteen, Poitier moved to the United States and stayed with an older sibling in Miami. A year later at the age of sixteen, Poitier moved to New York City; and it was here the Bahamian native developed the desire to act. However, he was faced with a supreme obstacle. The aspiring talent was unable to read. Despite his inability, Poitier was still determined to pursue the profession.

In the mid-1940s, he came across an ad in the New York Amsterdam News where the American Negro Theater announced the happening of an audition for a production. Poitier, who was employed as a dishwasher, had maintained his Caribbean accent and was still not astute in the literateness of the English language. At the moment, he did not see such an obstacle and pursued the audition. The audition was unsuccessful for Poitier, as his accent and inability to read the script did not post a positive impression on the theater’s owner, Frederick O’Neal.

In a 1959 profile piece with the New York Times, Poitier recalled the day, highlighting his determination to become versed in the English language.

“That was my day of decision,” said Poitier. “I was embarrassed, mortified, but most of all frightened because of my fatalities, my personality deficiencies, everything on the debit side of my ledger suddenly became crystal clear. I was determined to get rid of that accent and to show that man I could become an actor in no time.”

Poitier went on to study the English language and eventually he mastered it. According to the New York Times, he purchased a fourteen-dollar radio and spent hours listening and studying the voice of the North American accent, striving to enunciate words, and also vigorously studied the pronunciation of words and syllables through newspapers and magazines.

In a 2013 interview with Lesley Stahl on CBS Sunday Morning, Poitier detailed his time studying the language, crediting a waiter from the restaurant he was employed as a dishwasher, a Jewish man, as being instrumental in his unorthodox schooling of the language.

“One of the waiters, Jewish guy, elderly man. I had a newspaper and he walked over to me and he looked at me and he said, ‘what’s new in the paper?’ And I looked up at this man and I said to him, ‘I can’t tell you what’s up in the paper because I cannot read very well.’ He said, let me ask you something, ‘would you like me to read with you?’ I said to him, ‘yes if you’d like.’”

Every night for weeks, after the restaurant was closed, the elderly Jewish waiter sat down with a keen Poitier to read the newspaper with him where he learned a sufficient amount of understanding of the English language. It was this type of aid that triggered the infancy of Poitier’s acting career.

Poitier returned to the American Negro Theater and got the opportunity to take acting classes in exchange for the labor of doing chores in the likes of sweeping. Poitier became an understudy for another production titled Anna Lucasta, who was Harry Belafonte. He ultimately landed his first acting gig at the theater for an all-Black production titled “Lysistrata,” and was paid $75 a week. The production did not last on Broadway after four performances. He was then led to taking a screen test for the role of a racially discriminated doctor for the movie, No Way Out.

In his first credited screen role, the 1950 film No Way Out, Poitier played Dr. Luther Brooks, starring alongside star actors including Richard Widmark, Linda Darnell, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Mildred Joanne Smith, and more. Throughout the 1950s, he dominated the film industry as a widely favored Black actor becoming America’s first African-American movie star. He went on to achieve several pioneering accolades.

© Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved.

In 1959, Poitier became the first Black man to be nominated for an Academy Award in the category of Best Actor for his role as Noah Cullen in The Defiant Ones alongside co-star Tony Curtis, a Jewish man, who summarized the moment in his memoir recognizing the climate of the Academy at the time stating they “weren’t going to give an Oscar to a black man or a Jew.”

Poitier instantly became renowned as America’s first Black matinee idol as he was widely accepted among both Black and white audiences. White America honed no hesitation in accepting him into the mold of American entertainment and cinema. His success defied the odds of Black talent and was representative of the personal zenith of the Black man in America.

In 1964, Poitier made history as the first Black man to win an Oscar for Best Actor as a result of his outstanding performance in the film Lilies of the Field, where he played a traveling handyman who serves as an aid to nuns seeking to build their own chapel. Taking place during the height of the Civil Rights movement, Poitier’s win signaled Hollywood’s somewhat, willingness to include the stance of Black talent as being elite. There was a general sense of guilt for the color barriers set in place, perhaps, the notion of typecasting, the same once experienced by Hattie McDaniel, the said film industry was up for a groundbreaking moment as Poitier’s win signaled the need to allow room for additional Black talent.

© 1963 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Poitier took on a strategic approach with his career in cinema. It would have been remiss if he did not consider the lively climate of racial inequality. He intentionally played roles of Black characters who were dignified, upright, and ethical. He declared to never be positioned to portray a Black man who was in an inferior position adjacent to any white character. While Poitier was moved by such a conviction, there were portions of Black America who did not necessarily find Poitier’s presence empowering at all.

In a 1967 New York Times piece titled, “Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So,” Clifford Mason detailed his understanding of Poitier’s roles as being “a good guy in a totally white world” and expressed how Poitier’s characters are not stationed in reality as being Black men. They are typically left with “no wife, no sweetheart” and often are slated as an aid to “helping the white man solve the white man’s problem.” The portion of Black America who shared such thoughts about Poitier had desired to see him playing the role of a Black man in a Black man’s world. However, during the 1960s American cinema was not ready for stories tailored for Black audiences, hence Poitier’s rise in favor in white America. However, Poitier was not the type to jump ahead and challenge the quo in a radical sense.

“I live by a certain code. I have to have a certain amount of decency in my behavioral pattern,” said Poitier in his 2013 sit-down with Stahl.

In one of Mr. Poitier’s most iconic roles, as homicide detective Virgil Tibbs in the 1967 film, In The Heat of the Night, he delivered a memorable performance that promoted fomo throughout white audiences. There is a scene where Tibbs approaches a plantation owner for questioning and is slapped in the face by the racist owner named Mr. Endicott. Poitier’s character, without any hesitation, slaps Mr. Endicott back. Poitier vowed to the makers of the film to modify the script to include his returning slap for the sake of his standard of representing the Black man in an integral manner. In his 2013 interview with CBS, Poitier told Stahl that if he did not make such respect, he would be disrespecting black people all over the world. The scene garnered global empowerment, as even the likes of Nelson Mandela, who saw the film during his unruly imprisonment.

Again, Poitier was not the type of Black man in America who used a radical approach when it came to his endeavors. He was a practitioner of Dr. Martin Luther King’s non-violent philosophy during the height of the Civil Rights movement. He also contributed to the cause for freedom, justice, and equality as he attended the historic March on Washington in 1963 alongside Harry Belafonte where Dr. King delivered his revered “I Have a Dream” speech.

The following year, Poitier followed Belafonte on a mission to deliver a $70,000 cash donation to student activists of Dr. King’s Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee in Mississippi. This is the same Mississippi where a 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched by two white men approximately ten years prior. The climate in Mississippi for Blacks was still deemed among the most dangerous, making Belafonte and Poitier’s trip jeopardous.

After landing in Jackson, Mississippi, the two actors immediately made their way to the student activists in a car and their vehicle was attacked by those who appeared to be members of the Ku Klux Klan. The driver was forced into a high-speed chase and bullets were charged at the vehicle. Luckily, no one was harmed. Belafonte and Poitier were vigilant upon arrival and delivered the respective funds, but Poitier vowed he would never take a risk to travel below the Mason-Dixon line ever again.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. described Poitier as “a man of great depth, a man of great social concern, a man who is dedicated to human rights and freedom.”

Poitier, while he shared his concerns about society in rhetoric, he did not want his “black horse” persona to overshadow his acting career. He was not fond of his race being the nucleus of his presence nor was he in favor of the media asking him questions centered around race. During a press run in 1968, amid the happenings of the Chicago riots that erupted after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, Poitier was bombarded with questions concerning his stance on the event. Disgruntled with the press, Poitier responded to their damning inquiries with a request for respect.

“I am a relatively intelligent man. There are many aspects to my personality that you can explore I think very constructively. But you sit here and ask me such one-dimensional questions about a very tiny area of our lives. You ask me questions that fall continually within the Negroness of my life. You ask me questions that pertain to the narrow scope of the summer riots. I am artist, man, American, contemporary, I am an awful amount of things so I wish you would pay me the respect due and not simply ask me about those things.”

Many Blacks may also find Poitier’s response damning due to the empowering possibility of cinema’s most renowned Black actor to use such an opportunity to speak on behalf of the community. Poitier was not a politician. He found his duty to be a job of shattering the stereotype of the Black man in America. By this time, he has been accredited to several pioneering moments including being the first Black man to win an Academy Award for Best Actor, the first Black man to kiss a white woman on television (Patch of Blue 1965), and America’s first Black matinee idol.

Respectively, being the sole Black matinee idol, Poitier shattered stereotypes and built bridges that succeeding Black talents have managed to victoriously take advantage of.

As the 1970s emerged, so did the next phase of Mr. Poitier’s career. The blaxploitation era made its way in which the context of the genre was the opposite of what Poitier portrayed throughout the 1960s. The blaxploitation era honed a “for us, by us” motto by enforcing the expression of Black stories through unapologetic Black actors. In the mid-1970s, Poitier teamed up with fellow Bill Cosby and directed and starred in three crime comedy films including Uptown Saturday Night, Let’s Do It Again, and A Piece of the Action, maintaining his iconic relevance. He also touched base with directing in the 1980s and directed the Richard Pryor starred Stir Crazy.

In the Bahamas, Mr. Poitier’s career and victories became a symbol of possibility. Bahamians honed pride in the presence and travels of Poitier. He is a testimony to the reality of how the Black man from abroad can venture to North America and reach a level of success that goes beyond the expected. In 2012, Sidney Poitier was honored by the Bahamian commonwealth as the Paradise Island Bridge of Nassau was renamed after the pioneering icon.

Sidney Poitier is globally renowned as a Bahamian, African-American, and Black man who has made historical relevance to all Black people over the world. It is key to acknowledge his impact on the Black race, first and foremost. Sir Poitier’s poise as a professional in cinema was a lesson taught to all non-black practitioners of discriminatory racial bias, that a Black man is beyond capable of pursuing such an outlet. His achievements have opened portals in the scope of Black representation, allowing the course of variety to settle in. Black figures all over the world from Nelson Mandela to Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. bore witness to Poitier’s undeniable truth, ultimately making him an icon of the African diaspora.

Works Cited

Pryor, Thomas M. “A ‘Defiant One’ Becomes a Star.” The New York Times, 25 January 1959

Stahl, Lesley. “Sidney Poitier: The 2013 “Sunday Morning” interview.” YouTube, uploaded by CBS Sunday Morning, 9 January 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jPI5zev4Too&t=381s.

Schulman, Michael. “The Meaning of Sidney Poitier’s Historic 1964 Oscar.” The New Yorker, 12 January 2022

Mason, Clifford. “Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?.” The New York Times, 10 September 1967

McNiel, Liz and Adams, Abigail. “Behind Sidney Poitier’s ‘Slap Heard Round the World’ That Made History in 1967’s In the Heat of the Night.” People, 8 January 2022

Peniel, Joseph. “When Sidney Poitier risked his life for civil rights.” CNN, 11 January 2022

“Reporters Ask Sidney Poitier His Views on Race (1968).” YouTube, uploaded by UGA Brown Media Archives, 17 March 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oDZAZWOyQAA&t=2s.

“Sir Sidney Poitier in Nassau for Bridge Renaming Ceremony.” YouTube, uploaded by Magnetic Media, 17 November 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6uaEQHn0Tw&t=1105s.

- Professional Commerical Staging Artist T. Michelle Makes Her Mark: ‘I Should Be Good Enough’

- Sir Sidney Poitier: An African Diaspora Icon

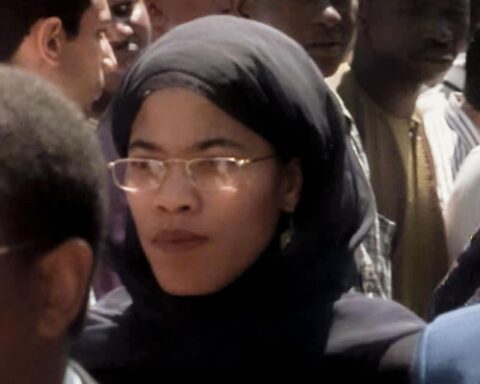

- A Daughter of the Struggle: Malikah Shabazz

- The Refinement of Park Hill: Kareem Woods’ Mission